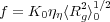

The viscosity of even dilute polymer solutions is usually far larger than just the viscosity of the background solvent, due to the large differences in size between the polymer and solvent molecules. In the non-free draining limit, we consider the polymer chain to move as an equivalent impermeable particle with an associated hydrodynamic volume that produces the same drag as the polymer chain. The friction coefficient is given by Stokes law as

where Rh is the hydrodynamic volume. The hydrodynamic volume is related in some way to the physical size of the chain, given by the mean square radius of gyration as

where αη is the hydrodynamic coil expansion factor.

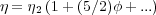

We will derive the Mark-Houwink equation starting from a basic consideration of the viscosity of a dilute suspension, as described by the Stokes equation for effective viscosity:

| (1) |

where φ is the volume fraction of particles in the system, given by the hydrodynamic volume of the polymer coils as

| (2) |

The specific viscosity and intrinsic viscosities, defined in Table 1 are readily derived from the Einstein equation, 1, as

![ηsp = (5∕2)(c∕M )NAVh

[η] = (5∕2)NAVh∕M (3)](handout5_w5x.png)

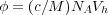

The hydrodynamic volume is given by

so the intrinsic viscosity is

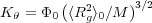

![( )

[η] = Φ α3 ⟨R2 ⟩3∕2∕M

0 η g0](handout5_w7x.png)

Φ0 is a constant which depends on the distribution of segments within the coil. A value of 3.67x1024 /mol is appropriate for non-draining Gaussian coils [5]. For Gaussian chains, the ratio of the mean square radius of gyration to the molecular weight is a constant, so we have

![3 1∕2

[η] = K θαηM](handout5_w8x.png) | (4) |

where

Equation 4 is called the Flory-Fox equation.

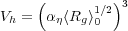

The hydrodynamic coil expansion factor scales roughly with M1∕10 so we further reduce this to

![[η] = KM a](handout5_w10x.png) | (5) |

where a is a constant between 0.5 and 0.8. Equation 5 is the Mark-Houwink equation. Calibration of the constants K and a for a particular polymer in a particular solvent at a given temperature allows determination of the molecular weight by simple measurement of the concentration dependence of the viscosity to yield the intrinsic viscosity. This is discussed in the next section.